Local fairs and carnivals have been around since the Middle Ages,

but modern amusement parks can trace their roots to the 19th century, when

so-called “pleasure gardens” and “trolley parks” first flourished in the United

States and Europe. These early resorts featured primitive—and often wildly

unsafe—roller coasters and rides, but they also included a variety of offbeat

attractions ranging from strongmen and wild animals to freak shows, staged

disaster spectacles and even battle reenactments. Take a trip through six of

history’s most enchanting and influential amusement parks.

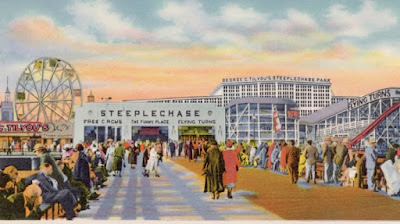

Steeplechase

Park

Opened in 1897 by entrepreneur George C. Tilyou, Steeplechase Park

was the first of three major amusement parks that put New York’s Coney Island

on the map. The park took its name from its signature attraction, a 1,100-foot

steel track where patrons could race one another on mechanical horses, but it

also included a Ferris Wheel, a space-inspired ride called “Trip to the Moon”

and a miniature railroad. While Tilyou intended Steeplechase to be the

family-friendly antidote to Coney Island’s seamier side, some rides still

ventured into territory that was risqué by Victorian standards. Attractions

like the “Whichaway” and the “Human Pool Table” tossed strangers against one

another and gave couples an excuse to canoodle, and the wildly popular Blowhole

Theater allowed spectators to watch as air vents blew up unsuspecting female

guests’ skirts. As the ladies struggled to cover themselves, a clown would

shock their male counterparts with a cattle prod. Fire destroyed much of

Tilyou’s park in 1907, but he responded by building a more elaborate

Steeplechase that remained in operation until the 1960s. Ever the showman, he

even charged ten cents for visitors to view the charred ruins of the original

park.

Vauxhall

Gardens

Opened in 1897 by entrepreneur George C. Tilyou, Steeplechase Park

was the first of three major amusement parks that put New York’s Coney Island

on the map. The park took its name from its signature attraction, a 1,100-foot

steel track where patrons could race one another on mechanical horses, but it

also included a Ferris Wheel, a space-inspired ride called “Trip to the Moon”

and a miniature railroad. While Tilyou intended Steeplechase to be the

family-friendly antidote to Coney Island’s seamier side, some rides still ventured

into territory that was risqué by Victorian standards. Attractions like the

“Whichaway” and the “Human Pool Table” tossed strangers against one another and

gave couples an excuse to canoodle, and the wildly popular Blowhole Theater

allowed spectators to watch as air vents blew up unsuspecting female guests’

skirts. As the ladies struggled to cover themselves, a clown would shock their

male counterparts with a cattle prod. Fire destroyed much of Tilyou's park in

1907, but he responded by building a more elaborate Steeplechase that remained

in operation until the 1960s. Ever the showman, he even charged ten cents for

visitors to view the charred ruins of the original park.

Dreamland

Coney Island’s Dreamland only operated for seven years between 1904

and 1911, but during that time it established itself as one of the most

ambitious amusement parks ever constructed. The brainchild of a former senator

named William H. Reynolds, the site included a labyrinth of unusual rides and

attractions lit by an astounding one million electric light bulbs. Visitors to

Dreamland could charter a gondola through a recreation of the canals of Venice,

brave gusts of refrigerated air during a train ride through the mountains of

Switzerland or relax at a Japanese teahouse. They could also watch a

twice-daily disaster spectacle where scores of actors fought a fire at a mock

six-story tenement building, or pay a visit to Lilliputia, a pint-sized

European village where some 300 little people lived full time. Dreamland

featured everything from freak shows and wild animals to imported Somali

warriors and Eskimos, but perhaps its most unusual offering was an exhibit

where visitors could observe premature babies being kept alive using

incubators, which were then still a new and untested technology. The infants

proved a huge hit, but they and many other attractions had to be evacuated in

May 1911, when a fire—ironically triggered at a ride called the Hell

Gate—leveled the property and shut Dreamland down for good.

Saltair

First opened in 1893, Saltair was a desert oasis situated on the

south shore of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The Mormon Church originally

commissioned the site in the hope of creating a wholesome “Coney Island of the

West” without the perceived sleaziness of the New York original. Their

family-friendly park proved an instant hit, as scores of visitors arrived by

train from nearby Salt Lake City to enjoy music, dancing and bathing in the

lake’s saline-rich waters. Saltair’s most striking attraction was its

gargantuan pavilion, a four-story wonder adorned with domes and minarets that

sat above the lake on more than 2,000 wood pilings. Along with touring this

“Pleasure Palace on Stilts,” visitors could also show off their moves on a

sprawling dance floor, ride roller coasters and carousels, and watch fireworks

displays and hot air balloon shows. The park boasted nearly half a million

visitors a year until 1925, when the iconic centerpiece burned in a fire. A

rebuilt Saltair opened soon after, but it failed to capture the magic—or the revenues—of

the original. The park closed its doors for good in 1958, and its abandoned

pavilion was later destroyed in a second fire in 1970.

Tivoli

Gardens

Denmark’s Tivoli Gardens first opened in 1843, when showman Georg

Carstensen persuaded King Christian VIII to let him build a pleasure garden

outside the walls of Copenhagen. Originally constructed on around 20 acres of

land, Carstensen’s creation featured a series of oriental-inspired buildings, a

lake fashioned from part of the old city moat, flower gardens and bandstands

lit by colored gas lamps. The park quickly became a Copenhagen institution, and

won fame for its “Tivoli Boys Guard,” a collection of uniformed adolescents who

paraded around the premises playing music for visitors. Tivoli later added an

iconic pantomime theater in 1878, and by the early 1900s it featured more

traditional amusement park fare including a wooden roller coaster called the

Bjergbanen, or “Mountain Coaster,” as well as bumper cars and carousels. Tivoli

Gardens was nearly burned to the ground by Nazi sympathizers during World War

II, but the park reopened after only a few weeks and remains in operation to

this day.

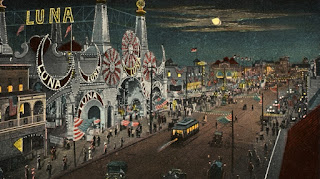

Luna Park

Founded in 1903 by theme park impresarios Fred Thompson and Skip

Dundy, Coney Island’s Luna Park consisted of a gaudy cluster of domed buildings

and towers illuminated by an eye-popping 250,000 light bulbs. The park

specialized in high concept rides that transported visitors to everywhere from

20,000 leagues under the sea to the North Pole and even the surface of the

moon. A trip to Luna could also serve as a stand in for world travel. After a

ride on an elephant, patrons could stroll a simulated “Streets of Delhi”

populated by dancing girls and costumed performers—many of them actually

shipped in from India—or take a tour through mock versions of Italy, Japan and

Ireland. If they grew tired of walking, visitors could relax in grandstands and

watch the “War of the Worlds,” a miniature, pyrotechnic-heavy sea battle in

which the American Navy decimated an invading European armada. The park’s

owners also cashed in on the popularity of disaster rides by staging

recreations of the destruction of Pompeii and the Galveston flood of 1900. The

carnage reenacted in these attractions became all too real in 1944, when Luna

fell victim to a three-alarm fire that began in one of its bathrooms. The

original site closed for good a few years after the blaze, but the iconic name

“Luna Park” is still used by dozens of amusement parks around the globe.

No comments:

Post a Comment